The United States does not have enough transplant kidneys to provide one to each person suffering from end-stage kidney disease who would benefit from a transplant. This shortage is costly to the people who end up waiting longer for transplant or who die awaiting one; to taxpayers, who pay most of the health care costs of people with end-stage kidney disease; and to the broader economy, which loses the talents of people suffering from kidney failure.

In 2022, U.S. hospitals performed 25,000 kidney transplants. About 6,000 of the organs came from living donors. Over 500,000 people are currently on dialysis and nearly 100,000 are on a transplant waiting list. An estimated 30 percent of transplants are pre-emptive: if not for the transplant, the recipient would go on dialysis.

Many good candidates for transplant are not placed on the waiting list. Some are discouraged from going to the trouble and expense of being evaluated to receive a deceased donor kidney. Some physicians hesitate to refer patients for evaluation to spare them the risks of some diagnostic procedures (such as a coronary angiography) and the disappointment of not being approved for the list. Most transplant centers use stringent criteria for placing patients on the list to increase the likelihood of successful transplants.

Dialysis is costly. Medicare spends nearly $100,000 per year for each dialysis patient it covers. It spent over $130 billion treating kidney disease in 2022. Private insurers also paid billions of dollars to cover the costs of dialysis for their enrollees. Patients with end-stage kidney disease constitute less than 1 percent of the Medicare population but account for 7 percent of the Medicare budget.

What’s more, the debilitating effects of kidney disease are not eliminated by dialysis, which is life-sustaining but imposes large costs. Most dialysis patients, regardless of age, find it makes them too fatigued to work. Dialysis patients also have a shorter life expectancy and greater health costs (beyond dialysis) during their remaining years than those who receive a kidney transplant.

The Living Kidney Donor

Support Act

In recent years there have been efforts to boost the number of kidneys available for transplantation. A promising effort is recent draft legislation called the Living Kidney Donor Support Act. It contains three major provisions to boost the number of kidneys from living donors.

Education campaign / The legislation would fund a national education campaign to inform the public about the need for kidney donations and opportunities to make living donations. It would note that donating a kidney is generally safe and publicize the benefits for the donor and recipient of saving a life through donation. This campaign would be run by a contractor and would train individuals and medical professionals in instructional outreach about the need for kidney donations.

One potential model for such a campaign is Be the Match, the federally contracted organization that operates the national bone marrow program. In addition to providing extensive information on its website, Be the Match offers information and support for potential donors throughout the country. It organizes informational sessions in numerous communities where someone needs a bone marrow transplant. After the presentation, the organization provides for testing people to determine whether they might be a match for the potential recipient and be added to the national donor database. If the potential donor is a match, he is asked if he wishes to explore donating. If so, Be the Match arranges for the initial tests. It also provides someone akin to a patient navigator (explained below) to help the donor through all steps from medical testing to marrow recovery (returning to normal levels of marrow after donation). Not-for-profit entities currently operate similar programs for kidneys on a local basis, but a national educational effort would be better.

Navigator office / The legislation would also create a living kidney donor navigator program. The program would train people to help potential donors, who often face time-consuming tests to determine their suitability for organ donation. Travel to testing sites can range from a few miles to hundreds of miles, depending on where the recipient is awaiting transplant. Having a navigator who could request that tests be done in a place convenient for the donor and streamline testing to avoid repeat visits to the transplant hospital could lessen the costs of donation.

Besides streamlining medical testing prior to surgery, a patient navigator could provide other assistance to donors before and after surgery. Navigators would be employed by federally contracted nonprofit organizations.

Several nonprofits already help facilitate kidney donations and have navigator-type staff. They are largely financed by private donations and to some extent by hospitals that receive the organs to do the transplant. Unfortunately, this assistance is not widely available throughout the country. The legislation would scale up these programs into a national system.

Reimbursing donors’ costs / The legislation includes a provision to reimburse donors for non-medical expenses incurred during the donation process. (Medical costs typically are covered by the recipient’s insurance.) Such expenses fall into three broad categories: out-of-pocket expenses such as food, lodging, and travel; lost wages during testing, the operation, and recovery; and childcare or elder care costs that a donor’s family may need during the transplantation process. Those expenses are discussed in more detail below.

Budgetary Effects

Each of the three provisions in the Living Kidney Donor Support Act calls for a government expenditure of some sort. However, because each provision would increase the number of kidney donors, they should save the government money on net. I estimate that the savings generated by moving people off dialysis—or keeping them off dialysis in the first place—greatly outweighs these expenditures, ultimately saving taxpayer money.

Educational campaign / The amount of money to be spent on an educational campaign would be specified by the legislation and the appropriations process, but it could also come from existing appropriated funds within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) budget. As a comparison, Be the Match reported in 2020 that it spent just over $23 million on public education efforts. The value of providing patient education to both the potential living donor and the potential recipient in directed donation cases has been documented and demonstrated to increase living donation. It is likely that either Congress will appropriate $25 million per year for the educational efforts called for in the Living Kidney Donor Support Act legislation, or HHS will use existing appropriated funds for these efforts.

Navigator office / The provision for a navigator office would entail having a trained professional—a nurse, counselor, or other health care professional—assist the donor throughout the donation process. Today about 7.5 percent of people who do an initial interview eventually donate a kidney.

To estimate the hours this would entail, I interviewed the directors of two programs that currently provide such services to prospective donors. Each described a similar process, beginning with an initial meeting with a prospective donor who typically has attended an outreach event held by the group and been identified as a potential match for someone in their community who needs a kidney. The initial meeting lasts about two hours.

If the potential donor decides to continue with the evaluation process, navigators counsel the potential donor on any medical concerns and the steps necessary. Navigators also make themselves available when the donor goes to the hospital for initial tests, which typically take between one and three days depending on the requirements of the transplant center.

Navigators help coordinate subsequent hospital visits as well and are in the hospital during and after the surgery. They are in regular contact with the donor during the entire process, and they meet briefly with the donor each day after the surgery that he is in the hospital, if requested.

Each organization remarked that the time put forth for each donor depends somewhat on the hospital. Transplant hospitals, which by regulation must provide living donor services themselves, strive to provide useful services and advice to prospective donors, which reduces the time navigators feel they need to spend with donors. Based on the interviews, I estimate that a navigator would spend 14–16 hours with each prospective donor.

The appropriate analogue for such a job in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics nomenclature of jobs would be clinical and counseling psychologists who work in medical and surgical hospitals. The reported average annual salary for such a position, converted to current dollars, is $110,700, or $2,130 per week. I estimate that the task requires approximately two full days per donor, which would translate to $850 per donor.

However, more than 30 percent of potential donors are ultimately unable to donate for medical reasons, and this determination often is not made until they are well into the process. To account for the cost of time spent with people who ultimately do not become living donors, I increased the cost per living donor by 50 percent, which is a reasonable estimate of the additional time that would be spent with that cohort.

That results in a total cost per donor of $1,275 for the proposed navigation process.

Reimbursing donors / The legislation would reimburse living kidney donors for non-medical expenses they incur throughout the donation process. These expenses fall under the following headings.

Travel and lodging. In a 2019 paper, Frank McCormick et al. estimated the aggregate costs of travel and lodging, lost wages, and dependent care to be $13,800 per person, the equivalent of $17,000 in current dollars. Their estimate for travel costs of $3,100 came from a 2014 report by the National Living Donor Assistance Center (NLDAC), which equals nearly $4,000 in today’s dollars.

The NLDAC provides funds to certain living kidney donors to cover a portion of their expenses in cases where the recipient’s income is below 350 percent of the HHS poverty guidelines and the donor meets a similar means test. The NLDAC reports that most donors must travel to the donation center at least three times before the operation, and they typically must remain near the center for one or two weeks afterward for monitoring.

The NLDAC caps reimbursement for travel and subsistence expenses at $6,000, so the data reported to them is truncated and may not be representative of the true distribution of such costs.

Other studies exist on the subject. Robert Gaston et al. produced a higher estimate of $4,300 for necessary travel and lodging costs ($5,300 in 2023 dollars) in their 2006 article in the American Journal of Transplantation. In contrast, James Rodrigue et al. estimated a cost of just under $2,000 ($2,500 in 2023 dollars) for travel and lodging costs in their 2016 American Journal of Transplantation article.

The NLDAC estimate was based on the largest sample size, 960 donors, and provides the most detailed accounting of donors’ expenses. Rodrigue et al. had a sample size of 181 donors, and Gaston et al. reported on 622 donors, for whom the authors did not have information as granular as in the NLDAC analysis.

I believe the McCormick et al. estimate, updated for 2023 prices, of $4,000 to be the most appropriate estimate of transportation and lodging costs for a kidney donor. It also happens to be the midpoint of the papers I consider to be most relevant.

Loss of income. Becoming a living kidney donor is time-consuming. The prospective donor must visit a hospital (usually the one where the surgery is to take place) either once for one to three days or multiple times for a variety of tests and interviews.

The donor typically stays in a hotel near the hospital the evening before the procedure and remains near the hospital for several days after the surgery. Most donors take at least two weeks off work for the procedure and recuperation. As donors must wait two weeks before driving, returning before then is a practical impossibility even for those in robust health post-donation. Rodrigue et al. found in their survey that the typical donor loses nearly a month of work from donating.

McCormick et al. examined the literature and determined the Rodrigue et al. paper to be the most comprehensive in compiling the value of lost income from a kidney transplant. Rodrigue’s detailed questionnaire determined that the average donor missed 180 hours of work, 40 percent of which was unpaid. McCormick et al. estimated the average cumulative cost of those lost wages to be $5,100 per person in 2017 dollars, or $6,300 in 2023 dollars.

Sebastian Przech et al. surveyed 912 Canadians who donated kidneys between 2009 and 2014 about the economic and other opportunity costs of donating a kidney. They estimated lost wages to be nearly $4,400 in 2017 wages, which would equal $5,400 today, broadly consistent with McCormick’s estimate.

In a 2020 rulemaking, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) assumed the median hourly wage (then $28 an hour, $33.09 in 2023) and multiplied it by 40 hours a week times the 4–6 weeks that donors are off work, which today equals $5,300–$8,000. I believe that the midpoint of the HRSA estimate—$6,650 per person—represents the best estimate of lost income.

Dependent care. Some prospective donors refrain from doing so because they are a primary caregiver for a young child or elderly parent, and the post-surgery recovery would keep them away from the house for several days (as would the time spent for evaluation, the surgery itself, immediate post-surgical recovery, follow-up appointments at the clinic, etc.). The surgery also constrains the physical tasks that a person can do for about a month after surgery. The Living Kidney Donor Support Act would provide funds to cover certain costs of childcare or elder care while the donor is unable to do those tasks.

The Przech study asked people whether they needed to obtain help to care for a dependent. Just over half reported they did. The average number of days for which they obtained assistance was 15, they reported.

The authors then assigned a daily wage to estimate the potential cost of providing such assistance. I use their estimate of the days a donor would need support and apply an updated estimate of the daily wage for elder care and childcare. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports those numbers to be $16.18 and $15.12 an hour, respectively. I assume that donors would need such services 24 hours a day for 15 days, with demand split evenly between childcare and elder care. The cost of such help on an hourly basis, estimated by simply using the average hourly wage rates, would be $5,630.

A 2021 nationwide survey by Genworth, a long-term care insurance provider, estimated the monthly cost of a home health care aide for 44 hours a week to be $5,148, or $5,900 in 2023 dollars. Full-time care—which would presumably be necessary for someone who did not have another caregiver living with them—would require four shifts for 15 days, or about half a month, which would be approximately $12,000.

A U.S. News and World Report survey of home health care providers found that average costs range from $12,000 to $16,000 a month, or half that—$6,000 to $8,000—for the half month that kidney donors require.

The HRSA rulemaking assumed childcare costs of $420 a week, which came from a National Center for Education Statistics 2016 survey. The survey reported an hourly out-of-pocket expense for primary nonparental care. For the entire transplant process of 4–6 weeks, it calculated total costs to be $1,680–$2,520, equivalent to $2,130–$3,200 today. However, the survey merely provided an estimated hourly cost for daycare and did not include any possible coverage for children outside of working hours, which I believe would be necessary for a postoperative donor. For that reason, I believe that $6,000 per person is the appropriate estimate for the cost of lost dependent care.

Aggregate estimate / Aggregating the estimates for transportation and lodging costs, forgone income, and dependent care costs during and after surgery yields a total estimate of the opportunity cost of donating a kidney of $16,650. Adding the $1,275 per donor cost of a navigator program yields a total of $17,925 per person. In comparison, in 2018 the average NLDAC recipient received $2,300 (in 2023 dollars), and 9 percent of living donors received money from NLDAC.

Health Effects

I also project how much living kidney donations would increase if all expenses for kidney donors were covered. Few studies have contemplated the elasticity of supply of kidneys from living donors, but some economists have tried to measure how much removing the barriers to donating a kidney would increase donations. McCormick et al. analyzed three different studies that examined programs where the government reduced the opportunity costs of donating a kidney and observed the resultant increase in donations.

In one of those studies, Kurt Schnier et al. examined the effect that the creation of the NLDAC in 2007 had on donations. At first it did not cover lost income or expenses, and its grants for travel and lodging were modest—averaging just over $3,000—and could only go to donors if their income and the income of the recipient were both under 300 percent of the poverty level. Schnier estimated that the program boosted kidney donations by 14 percent and attributed 532 additional donations to the program’s existence. McCormick used that analysis to estimate that fully covering all costs for all potential donors would result in nearly 10,000 additional kidney donations, which would effectively triple the number of live donations in a year.

McCormick et al. also looked at data from New Zealand’s program for kidney donations, which covered $5,000 of expenses and was associated with a 22 percent increase in donations. Extrapolating from those data, they estimated that removing all costs for potential donors would boost U.S. donations by about 9,500 per year.

Finally, McCormick looked at the data from Israel’s generous program that more fully compensates living donors for their costs—explicit and implicit—from donating a kidney. They valued the benefits provided at $37,745, which is what they ascertained to be the true opportunity cost of donating a kidney in the United States. The implementation of the Israeli program boosted living kidney donations by 231 percent; applying a similar response to the U.S. market would result in 13,400 additional donations.

McCormick et al. took the U.S. estimates from those three studies (along with an estimate from a 2010 paper by Scott Halpern et al. based on contingent valuation via surveys) and used the resultant average—11,500—as their estimate for the number of additional kidneys that would be donated if the United States were to fully compensate donors. Excluding the Halpern study gave an average estimate of 10,900 additional donations. I use the latter number in my fiscal analysis below.

Budgetary Effects

The increase in kidney donations from the Living Kidney Donor Support Act would result in some expense, but the accompanying savings for the federal government from moving people off publicly funded dialysis or avoiding dialysis in the first place would be significantly larger.

Additional costs of reimbursing donors / I estimate that increasing reimbursement of living kidney donors for their out-of-pocket expenses and lost wages while also paying for a navigator program would result in an average estimated cost of $17,925 per donor. These benefits would increase donations from living donors from approximately 6,000 to 17,000 annually. The cost of these payments would amount to $305 million per annum. Currently, the NLDAC spends $12 million a year reimbursing kidney donors, so the incremental spending would be about $293 million per year.

These payments would also increase the number of kidney transplants performed, most of which would be paid for by the federal government, generating additional costs. The average kidney transplant costs $133,000, and Medicare pays for 79 percent of all kidney transplants performed. The cost of the 11,000 additional transplants amounts to $4.84 billion a year, and the federal government’s additional cost would be $3.73 billion. Accordingly, the 10-year cost would be $37.3 billion.

More kidney donors would mean more people with a transplanted kidney. Recipients must take immunosuppressants to prevent their rejecting the new organ. These drugs cost $25,000 a year, and McCormick et al. estimated that the total annual health care costs associated with a kidney transplant is $34,000 per recipient.

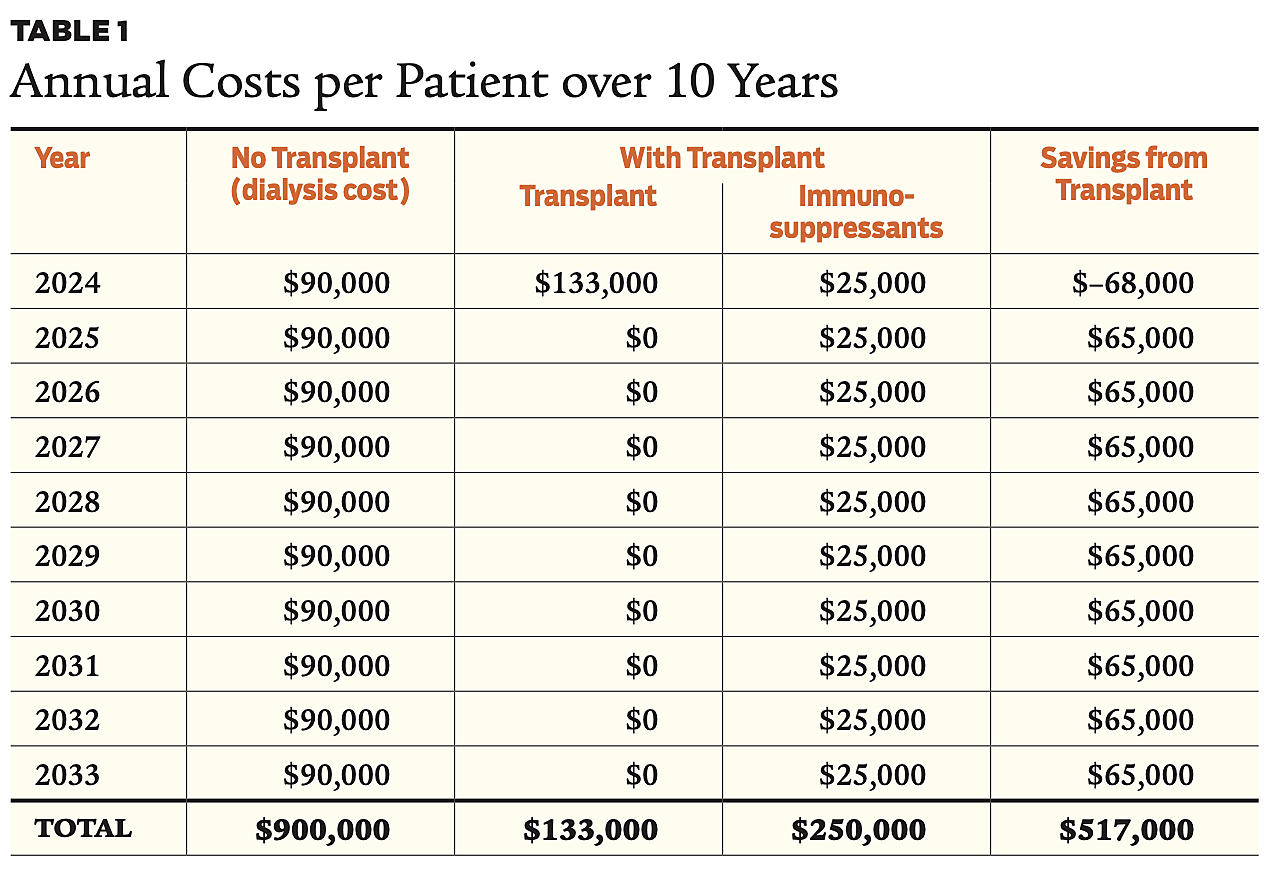

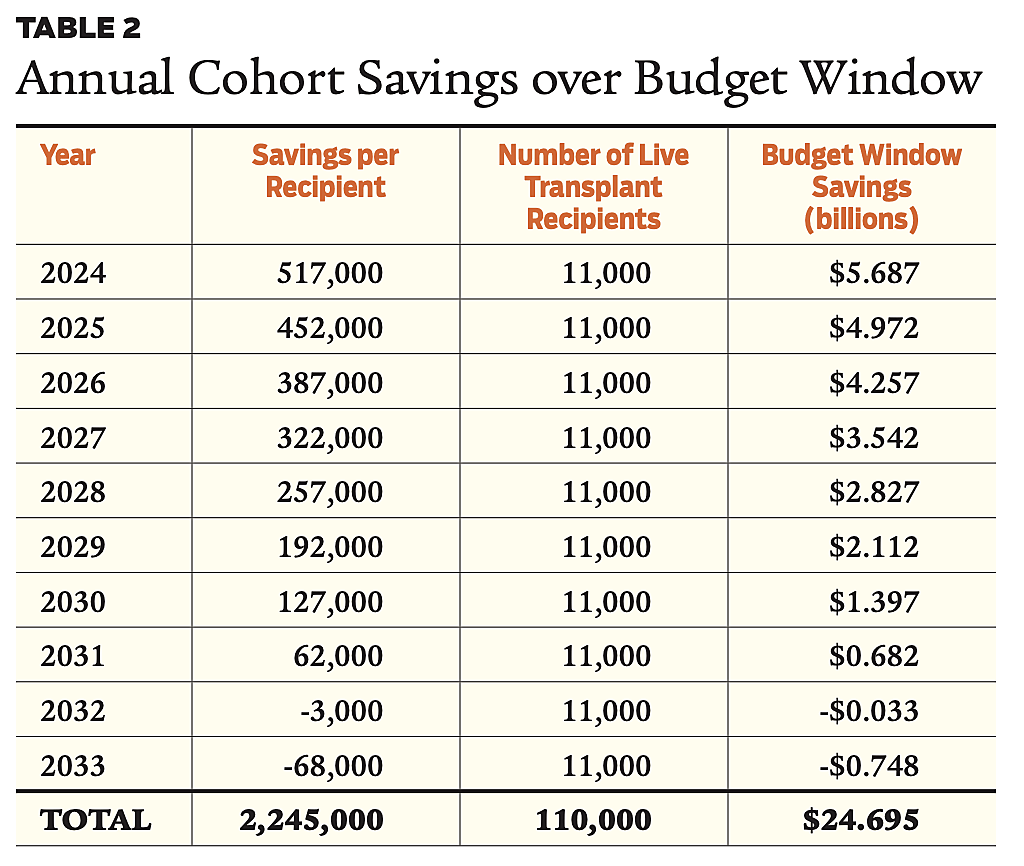

In Year 1, the budgetary calculus is simple: transplants cost $133,000 and immunosuppressants cost $25,000, while dialysis costs $90,000 a year. That means that in Year 1 the government pays $133,000 per transplant and $25,000 for immunosuppressants but stops paying dialysis costs. For the next nine years, it continues paying for immunosuppressants instead of dialysis, realizing $65,000 in savings each of those years of the budget window. In essence, this would pay off the transplant in two years and produce eight years of savings, or just over $500,000 apiece for 11,000 people, within the budget window. Tables 1 and 2 show the arithmetic for the cost savings.

In Year 2 of the budget window, there would be an additional 11,000 transplants, generating the equivalent of seven years of savings in the 10-year budget window for this cohort. This would thus save $512,000 – $65,000 = $447,000 apiece for the 11,000 people. Year 3 would realize savings of $382,000 apiece for 11,000 additional live transplants; Year 4 would have $317,000 in savings multiplied by 11,000, and so on.

Table 1 sums the net savings over 10 years from each of the cohorts. For the cohorts that receive transplants in Years 9 and 10, the budget savings within the 10-year budget window would be negative. The total savings from reduced need for dialysis would be approximately $24.1 billion over the 10-year budget window. Since the government pays 79 percent of all dialysis and transplant costs, the total savings to the government would be $19.1 billion.

The cost of the program would be the defrayment of costs for all the 17,000 estimated living donors each year under the Living Kidney Donor Support Act. This includes the 11,000 additional donors per annum and the estimated 6,000 annual donations that would have occurred regardless of any cost defrayments.

I estimate that the average cost of reimbursement, along with the cost of the navigator program, would be $17,920 per person. Providing this amount for each of the 17,000 living kidney donors would total $293 million per year, or $281 million of incremental spending. If we assume the cost of an informational campaign would be $25 million a year, the combined annual expense of cost reimbursement, the navigator program, and accompanying informational campaign would be nearly $300 million a year, or $3 billion over the 10-year budget window. Subtracting this cost from the savings to the government from reduced dialysis gives us a 10-year budget savings of $16 billion.

Conclusion

Enacting the Living Kidney Donor Support Act would substantially increase the number of transplant kidneys. I estimate that the law would substantially reduce government spending on dialysis, and the budgetary savings would equal $16 billion over 10 years once the program is fully operational.

Readings

- “Direct and Indirect Costs Following Living Kidney Donation: Findings from the KDOC Study,” by J.R. Rodrigue, J.D. Schold, P. Morrissey, et al. Journal of Transplantation 16(3): 869–876 (2016).

- “Financial Costs Incurred by Living Kidney Donors: A Prospective Cohort Study,” by Sebastian Przech, Amit X. Garg, Jennifer B. Arnold, et al. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 29(12): 2847–2857 (2018).

- “Limiting Financial Disincentives in Live Organ Donation: A Rational Solution to the Kidney Shortage,” by R.S. Gaston, G.M. Danovitch, R.A. Epstein, et al. Journal of Transplantation 6(11): 2548–2555 (2006).

- “Regulated Payments for Living Kidney Donation: An Empirical Assessment of the Ethical Concerns,” by Scott D. Halpern, Amelie Raz, Rachel Kohn, et al. Annals of Internal Medicine 152(6): 358–365 (2010).

- “Removing Disincentives to Kidney Donation: A Quantitative Analysis,” by Frank McCormick, Philip J. Held, Glenn M. Chertrow, et al. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 30(8): 1349–1357 (2019).

- “Subsidizing Altruism in Living Organ Donation,” by Kurt E. Schnier, Robert M. Merion, Nicole Turgeon, and David Howard. Economic Inquiry 56(1): 398–423 (2017).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.